Fall in love with the problem

weak coaching or scientific method?

Read in Portuguese

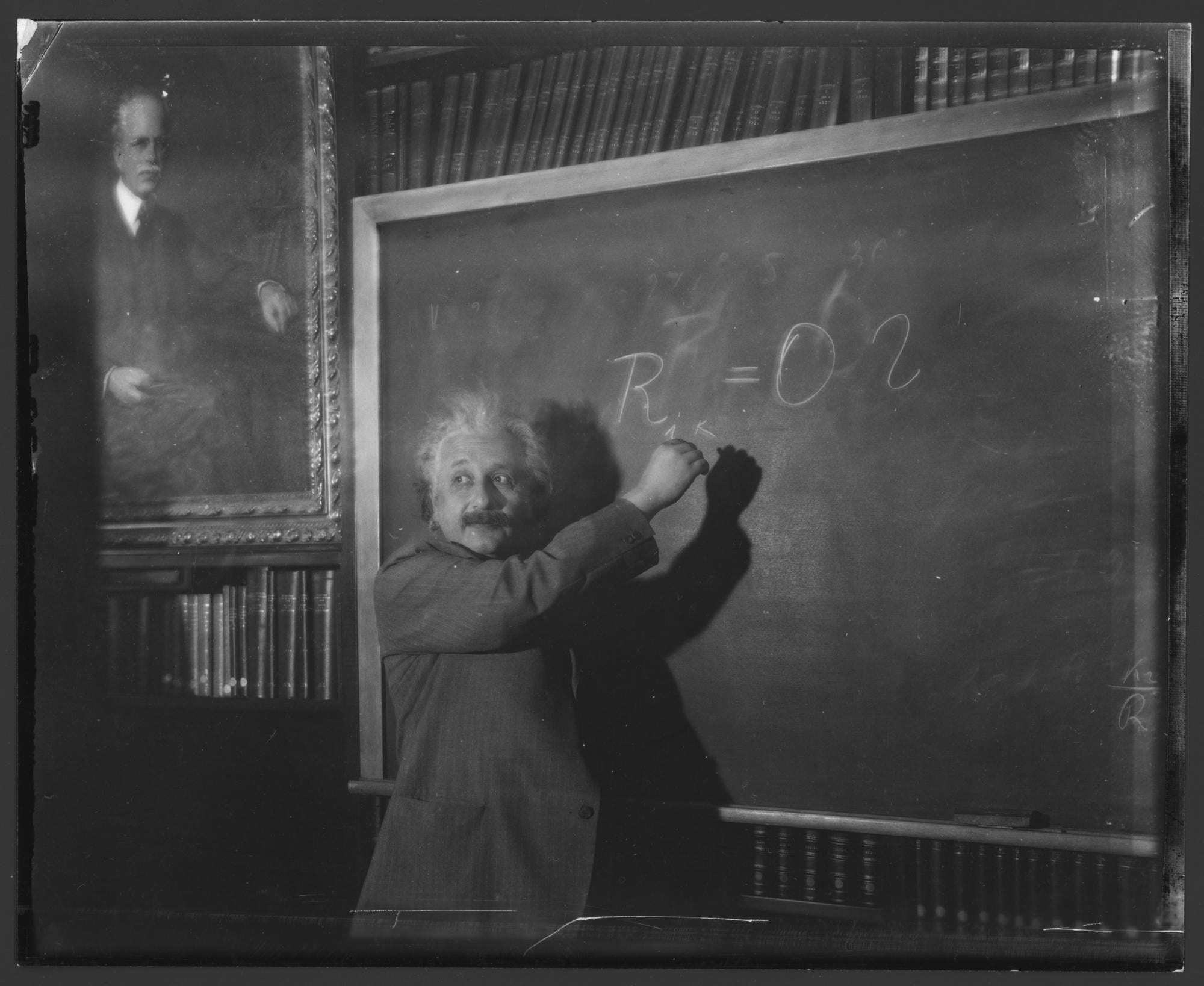

Albert Einstein, at the blackboard in the Hale Library, Pasadena. Image courtesy of the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

There is a phrase that has circulated for decades among designers, engineers, and entrepreneurs:

"Fall in love with the problem, not the solution."

It often sounds like a slogan. Almost a talk mantra. But, when seen more carefully, it points to something much deeper - and scientifically solid.

In other words, that phrase says the following:

Understanding the problem is half the solution.

This is science.

What computer science has to say about it

In computer science, especially in the study of algorithms, there is a central concept called correctness.

Proving that an algorithm is correct does not just mean showing that it "works in practice". It means demonstrating, rigorously, that it solves exactly the proposed problem - for all valid cases.

And here is the crucial point:

There is no correctness proof for a poorly defined problem.

Before any line of code, any data structure, or any optimization, two fundamental questions must be answered:

- Which inputs are allowed?

- Which properties must the output satisfy?

These two things form what we call the problem specification.

Without that, there is no correct algorithm. Only accidental behavior.

As made clear in the following passage:

Problems specifications have two parts: (1) the set of allowed input instances, and (2) the required properties of the algorithm's output. It is impossible to prove the correctness of an algorithm for a fuzzily-stated problem. Put another way, ask the wrong question and you will get the wrong answer (Steven Skiena, 2020).

It does not matter how elegant the code is. It does not matter how advanced the model is. If the problem is wrong, the solution will be too.

The classic mistake: rushing to the solution

In professional practice, what we most often see is the opposite.

- Companies in love with tools

- Teams in love with architectures

- Professionals in love with frameworks

- Startups in love with features

All of this before deeply understanding the problem.

The result?

Technically sophisticated solutions answering the wrong question.

In computing, this generates incorrect algorithms. In the real world, it generates useless products, empty metrics, and expensive systems to maintain.

Understanding the problem is active work

Understanding a problem is not passive. It is not "listen to the brief" and move on.

It is active work of:

- defining boundaries

- eliminating ambiguities

- making assumptions explicit

- asking uncomfortable questions

- rejecting premature solutions

That is why good engineers, scientists, and strategists take longer at the beginning - and speed up later.

They know that every minute poorly spent understanding the problem turns into weeks of rework trying to fix the solution.

So, "fall in love with the problem" is not poetry

It is method.

It is intellectual discipline.

It is recognizing that the hardest - and most valuable - part of the work is not building the answer, but formulating the right question.

In computer science, that defines the correctness of an algorithm. In business, it defines the relevance of a product. In strategy, it defines the clarity of decisions.

In the end, solutions are replaceable. Frameworks age. Technologies change.

But the ability to deeply understand a problem remains one of the rarest - and most valuable - skills anyone can develop.

References

- Skiena, S. S. (2020). The algorithm design manual (3rd ed.). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54256-6